"Landscapes can be leading characters themselves, and the people in them the extras." Wim Wenders

This principle appears subtly in Bagdad Cafe, where the isolated desert truck stop functions as a transformative oasis—a space where the normal rules of reality seem temporarily suspended. In Paris-Texas, cinematographer Robby Müller transforms the American desert into an extension of Travis's internal desolation.

The desert setting in both films creates a "liminal zone"—a space between civilisation and emptiness where characters become untethered from their former identities. The visual void of endless highway or barren landscape creates psychological permission for transformation to occur.

Both films reject naturalistic colour grading in favour of deliberate chromatic choices that function as emotional language rather than documentation. They also centre on an outsider arriving in an unfamiliar landscape, and this outsider becomes the focal point through which transformation occurs.

These 2 films feel like a direct transmission of internal states: disorientation, isolation, longing, transformation, and grief.

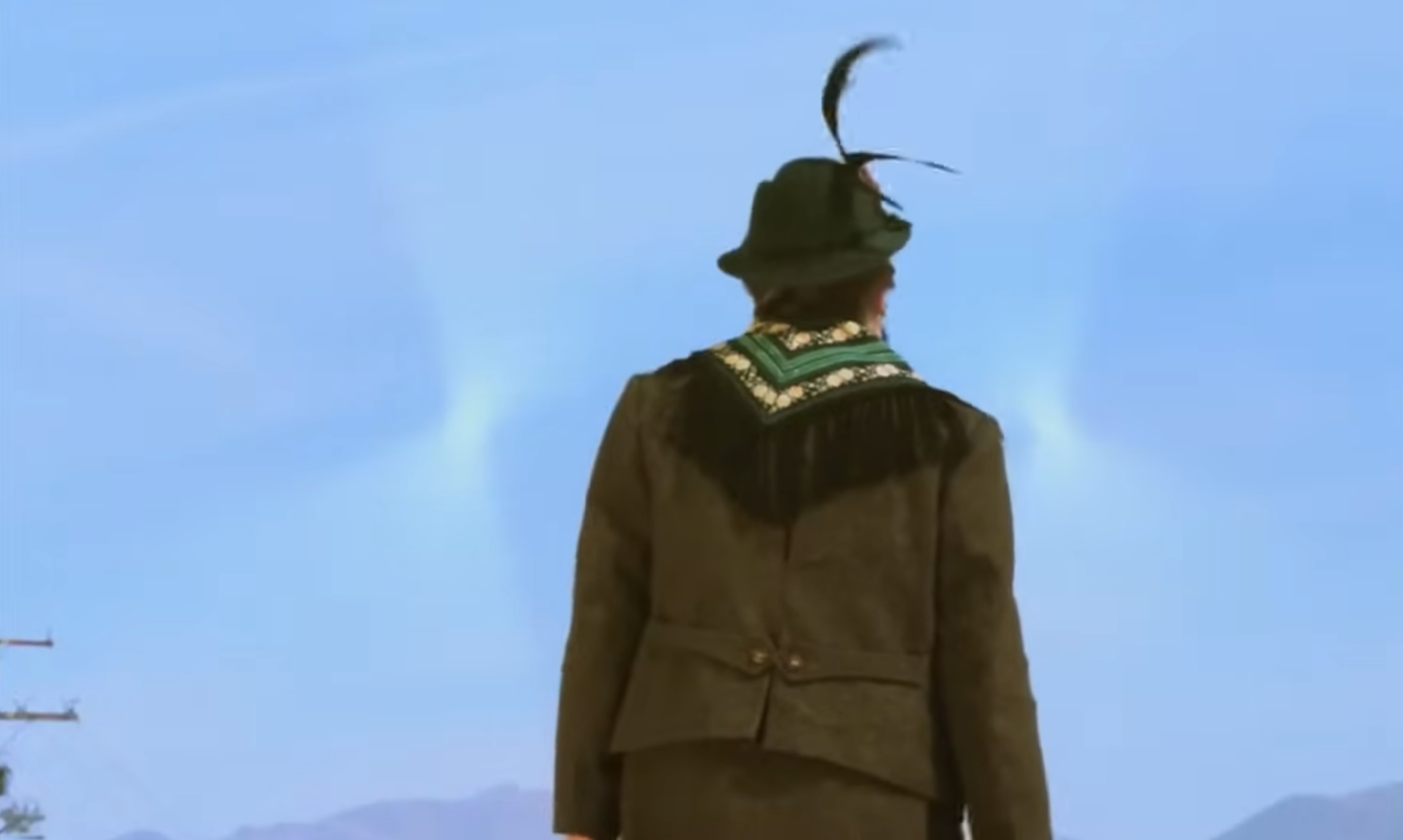

BAGDAD CAFE

1988

Director Percy Adlon

Jasmin is a displaced German tourist who arrives at a remote American desert café and somehow catalyses grace and harmony among its fractured inhabitants. Her foreignness is essential—she sees the world differently, and that different vision allows others to see themselves anew. The transformation is gentle, almost magical.

You can watch the movie here

PARIS, TEXAS

1984

Director Wim Wenders

Screenplay Sam Shepard

Screenplay Sam Shepard

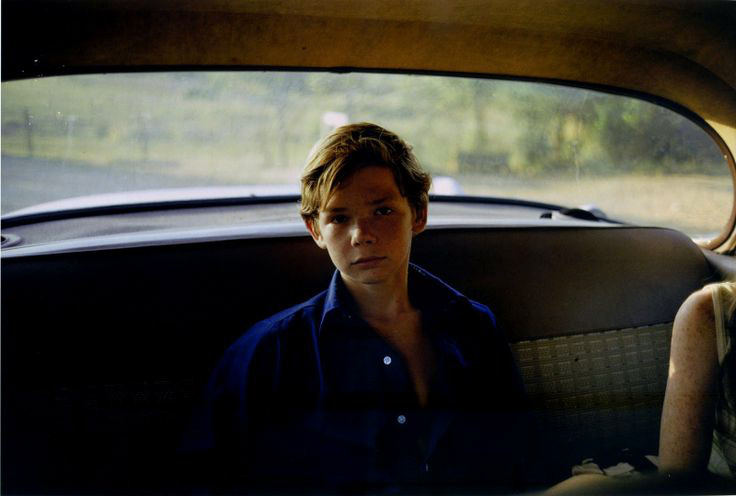

Travis is a stranger returning to a landscape (Texas) he once inhabited but no longer understands. He moves through spaces as an observer, looking in from windows and through glass, unable to truly reconnect. His isolation is irreversible; the film suggests that some separations cannot be healed despite proximity.

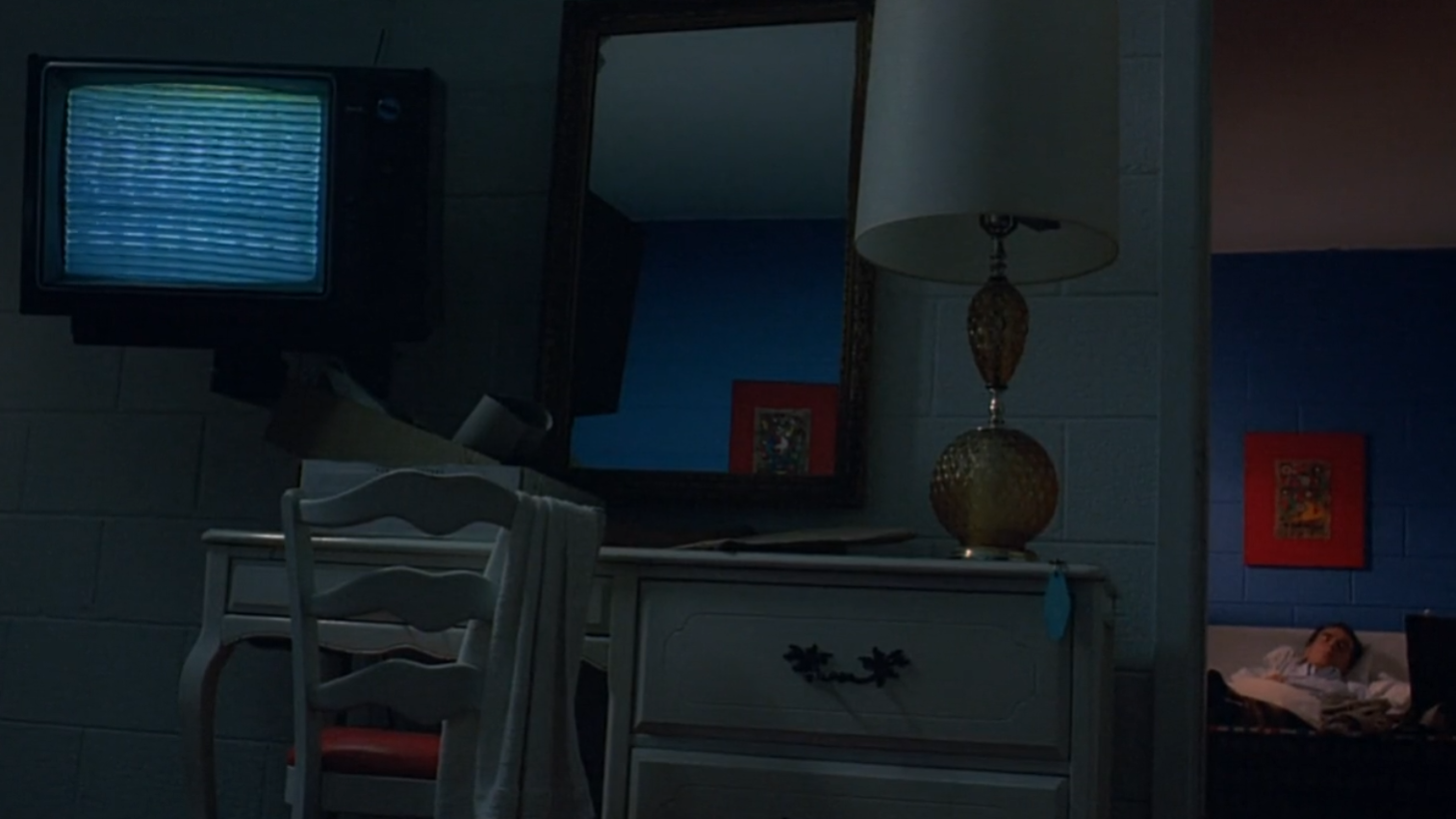

Both films feel as if Hopper’s diners and motels had suddenly started to move and talk: islands of fluorescent light at the edge of the desert where people share space but remain sealed in their own inner rooms.

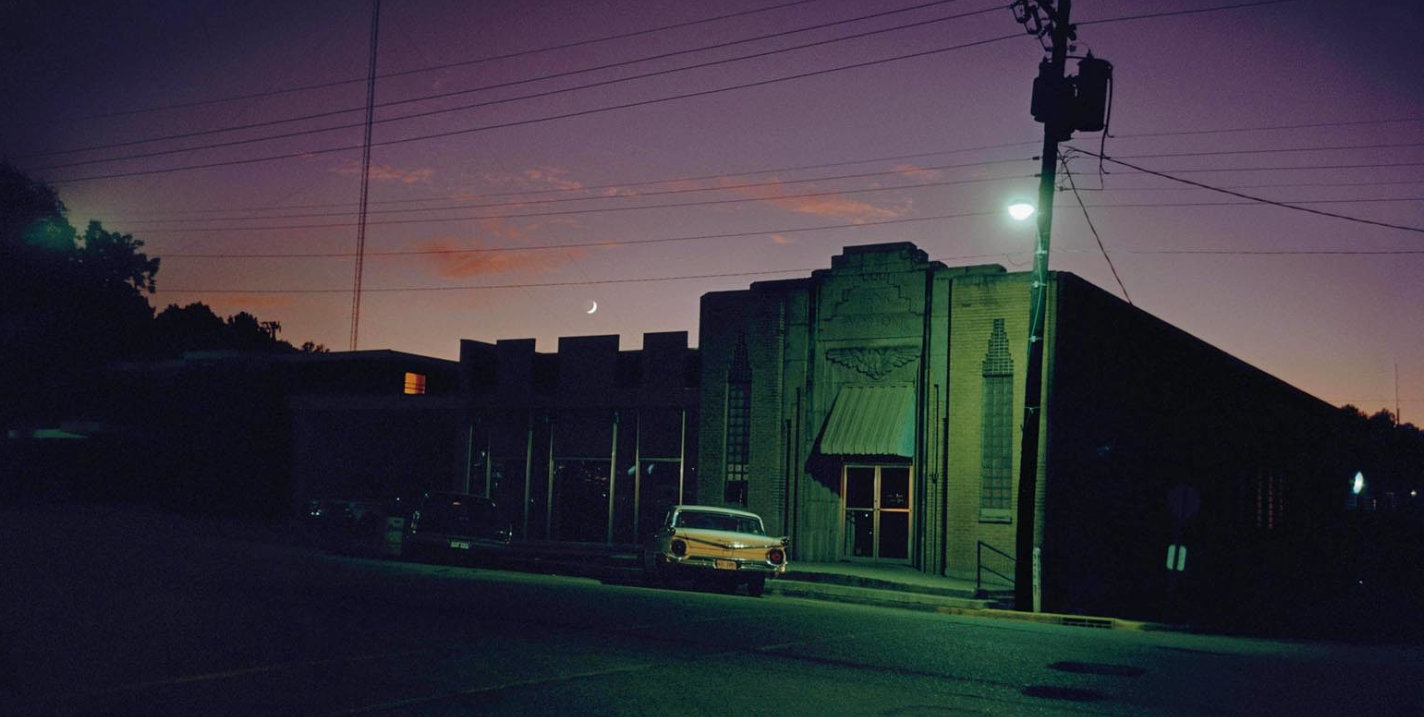

If Hopper gives these films their architecture of loneliness, Eggleston gives them their chromatic skin: the sodium‑yellow cafés, neon‑soaked motels and sun‑blasted parking lots that turn low‑rent roadside America into something strangely luminous and haunted.

If Hopper gives these films their architecture of loneliness, Eggleston gives them their chromatic skin: the sodium‑yellow cafés, neon‑soaked motels and sun‑blasted parking lots that turn low‑rent roadside America into something strangely luminous and haunted.